This is the shape of the world

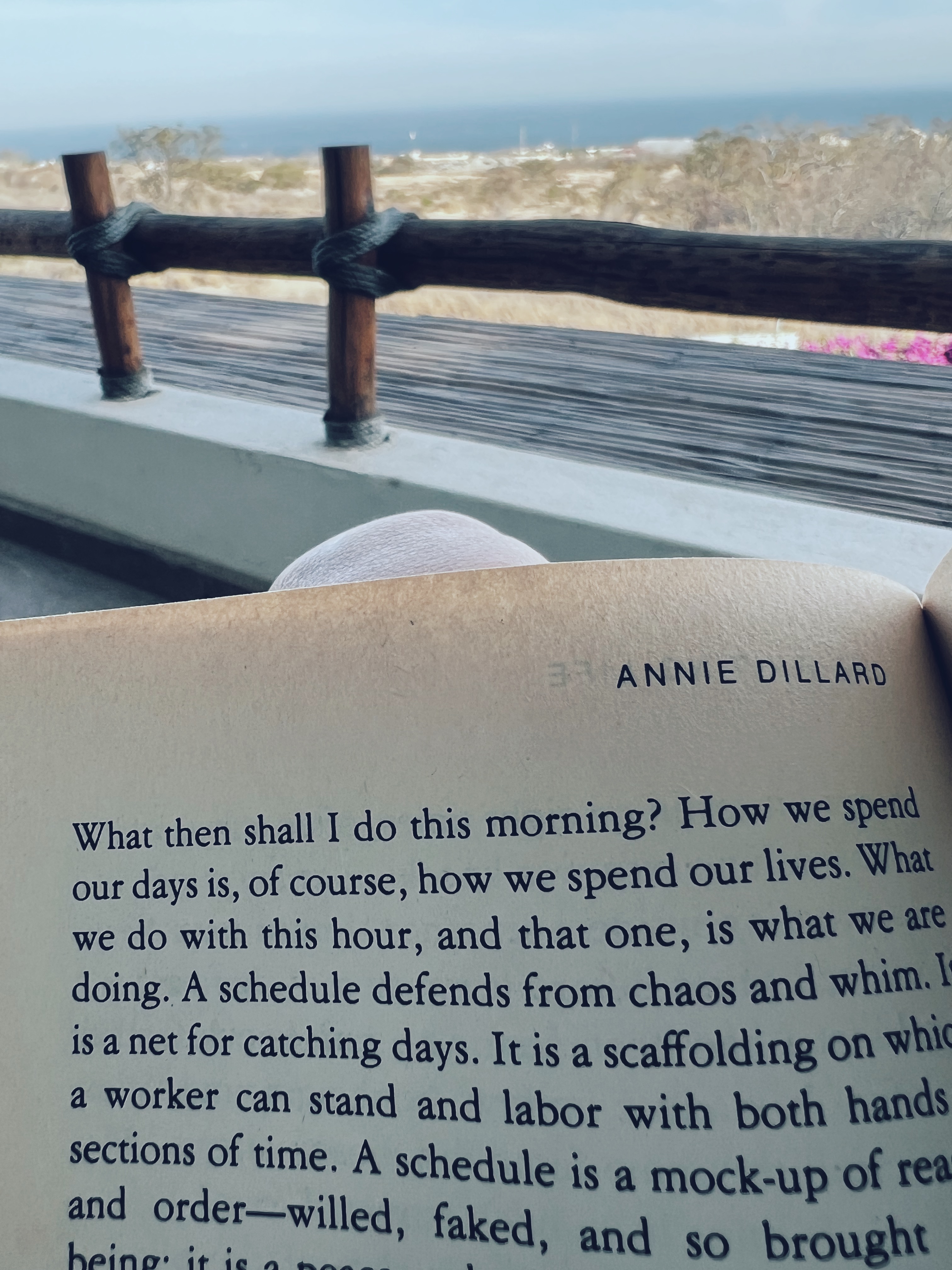

We only get so many hours on earth. A finch laid five eggs. I write my poems and try to spend my time wisely while we wait for the world to get good.

I’ll likely spend upwards of six hundred ten or twenty thousand hours on earth in this particular body. This spectacular body! Miraculous vessel, occasional hovel. This shape I’ve made my own, amen. I intend to use my hours well. I do not care to be careless.

Also I do not care for math, but I’ll do it when I need to. In this case, to count my blessings—all these hours, and to remind myself the stakes—we only get so many.

I’ve used up about three hundred and fifty six thousand of them already, maybe one hundred thousand sleeping. I wouldn’t sacrifice a single one. Rest is so important.

Of the two hundred and fifty six thousand or so hours I’ve spent alive and awake, how many have I spent aware?

How many have I spent scraping the bowl, bending myself backwards to accept lousy love, letting myself rot, mindless, scrolling, disassociating, talking mean to me, making bad medicine?

I ask not because I’m looking to make me or anyone else feel like an asshole, but because I’m curious how much time I’ve stolen from myself and how much has been stolen from me.

How much has the world, designed as it is, been designed to keep me distant from myself and others? To keep me anxious, tired, angry, hungry, guilty, confused, complacent?

How much have I, consciously or not, chosen empty engagement? Conversations I didn’t really want to have with people I don’t think were listening, mediocre television served up six to twelve hours at a time, scrolling the sale section of a half-broken website, downloading and removing apps, updating my passwords, updating my operating system, wondering if someone who was wrong on the internet has learned how to be right yet, wondering if someone who was cruel on the internet has been shamed into decency, envying homes I can’t afford, wishing an era of implacable, unnameable, simmering discomfort on those who have wronged me.

I’m not sure all those hours were meaningless, but I’m sure I don’t need many more of them.

And of the two hundred and fifty six thousand or so hours I’ve spent alive and awake, how many have I loved? How many can I remember? Plenty. Enough. Never enough. I’m trying my best to be here.

I’d like to make of my time something living.

It’s such a pleasure to be of this earth, an honor, a miracle really, to be here at all, and right now too, with you? Unlikely. I’m on the verge of doing math again, but I don’t want to, so consider this short story about some finch eggs instead:

A few weeks ago, I seen a freshly assembled cupped bird’s nest tucked into the clematis vine climbing a trellis leaned against a beam in the back patio. The pear trees and locusts had just started to bloom, the clematis not yet greening. It was still early spring and the snow hadn’t yet finished. Some nights it still fell below freezing.

Soon after I seen the nest, I spotted the pair of house finches who’d built it. They did a good job and the nest was sound, twigs and dry grass braided tightly with leaves and old feathers, shrouded in a tangle of climbing vines, a helpful guard against April winds.

I tried to be respectful. I peeked in the nest only thrice. The first time, I made out a single egg and learned a finch will lay one a day; once finished, the eggs take two weeks to hatch. A few days later I checked again—five eggs now. After that, the hen spent most hours in the nest. I gave her space, and checked on her daily. Her mate favored foraging in the nearby plum and juniper trees, favored also by scrub jays, towhees, blue birds and robins, wrens, chickadees and sometimes magpies. The afternoons were full of birdsong and scuffle.

About ten days in, I noticed the hen hadn’t been in her nest all morning. In fact, I hadn’t seen her in a day, maybe two. I studied the clematis, just starting to green, and felt immediately something was off. The trellis seemed jostled, the nest loosened. I pulled over a chair to stand on so I could peek in one last time. Every egg was gone.

There was not a single trace that a single egg, let alone five, had ever existed, in the nest or on the ground. At least none I could sense. Some birds tussled unseen in a shrub nearby. Maybe they were squirrels. The other day, Kyle saw a hawk in the cottonwood over there. The crows gather throughout the day. Seasonal migration has brought 3.5 billion birds flooding back into the changing sky.

Everything comes to life in spring. Everything has to eat.

The point is that small, lovely songbird laid five eggs in early spring with the snow unfinished and not a single egg hatched. She’ll build another nest and lay another four to five clutches before fall. One in three hatchlings will survive to adulthood.

Do you know how unlikely a finch is?

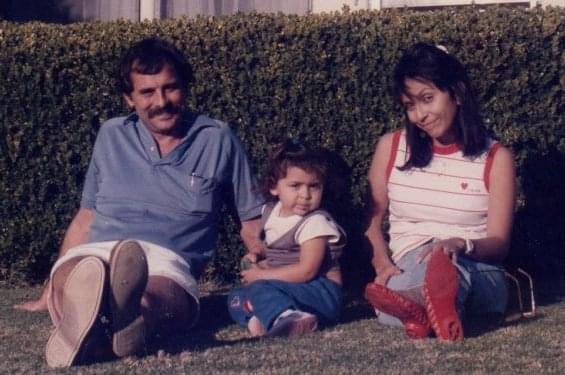

How unlikely it is that my father, born in Saint Louis, Missouri to fourth generation German-Americans, who carried a broken heart to California in the early 1980s, would meet and marry my mother, born and raised right there, a first generation Mexican-American in a land that used to be Mexican and before that unbordered, peopled by my grandfather’s—which is to say my—ancestors, who survived. How unlikely they had a daughter, who is me, who has spent so many hours scrolling, seething and self-loathing, who despite all the distraction got me here, forty years and five thousand five hundred and twenty seven or so hours old, who knows you who is reading this, somehow, some way?

Everything’s miraculous and I’m counting my hours. I never said I was perfect. Just unlikely.

Unlikely as I am, I find joy in small things. How many hours I’ve spent looking at trees. Talking to other animals. Learning to name living things. Making little altars wherever I go, making a nice plate of snacks. I wrote my first poem when I was nine years old and kept doing it, as much as I could, through high school, college and into graduate school—I got paid for a year to read and write poems. Those were hours well spent. I took about eight years off between 2012 and 2020, which was foolish but fine. I’ve been making up for lost time.

Since last October, I’ve had sixteen poems published in thirteen different journals, with another ten pieces in four spots on the way. I received my first Best New Poets nomination from Frozen Sea, which was nice, and was named one of five finalists for this year’s Porter House Poetry Prize. A few weeks ago Ballast Journal published a poem I first wrote over a decade ago and spent hours over months and years fiddling with to make it what it is. This morning I woke up and read it for you.

I’ve been trying to mold my days into a life I can live with. I notice what I can and grieve what I must and welcome the changing sky. I keep love close around me and treat my attention as something sacred. I hope you can too.

I hope you’re able to keep yourself and other living things alive today.

I hope you love every hour you can.

I hope we live to see a more loving future.

Given enough time, all the hours in the world, it seems likely it’s on the way.

A brief history of everything

Such a thing exists as knowing. We demand

more than mere belief.

What is known:

Time passes.

Sky’s blue.

You wind your watch every morning

& take your coffee with milk.

Before knowing there was nothing—

a hollow, a shape that wants,

id est, it lacks,

just like the rest of us,

calls in silence for knowing.

There was a time—can you believe it?—

when I didn’t know your name.

In the beginning, there was wanting.

Then language— the word itself,

“want”—

a seminal rebellion.

To agree a beginning must have been

is to sense an end must be.

We name what comes between

& in so doing, give it texture.

You call me love,

I feel its gravel.

I’ve called you foolish

(this is a whim).

To name is not enough.

There needs a weight,

an understanding

not just the sound one mouth makes

toward another

but its gravity

(a constant bearing down).

To know I think is bleeding,

see, we feel

the world in friction

measure

learning in the wounds.

A voice can say so much. A force can test

a shape, compel it toward

another.

There is for every venturing a consequence in space.

This is the shape of the world. This is the heart

in your hand. I asked you once

where I began,

assuming you could not be far behind,

& when we may have become

us.

You think I’m occasionally

unreasonable, yet

indulge me all the same.

Consider— what is knowing

is only wind

or breath & stone

or earth

& skin—

that the whole of what we’ve known

can be carved into a rock

& turned to ash again.

I make diagrams in a book you gave me,

keep it close for reference, to recall

how strange it is

I know you.