What returns love

I had a brief, bright infatuation with a feral squash, meanwhile the world keeps spinning. Here's a poem by Louise Glück.

I am delighted by volunteers—plants that germinate and flourish entirely on their own, no human hand to mind them.

For years, chamomile volunteered itself across the container garden on our back deck, blooming spring after spring and deep into autumn, growing even in the gutter, sneaking in with the thyme, producing jar after jar of home-dried tea to enjoy and enjoy giving to friends. It needed so little to offer so much. A bit of space to grow and not too much fuss.

The aphids came for it this year. Sucked it dry while we were in the desert. These things happen. We had a nice arrangement, and it was lovely while it lasted. I tend to be romantic about what’s beautiful and doomed.

It’s just what we’re often so quick to call a weed is a living thing that moved into a room of opportunity. Who am I to begrudge that? Consider the dandelion. One of the most useful plants on the whole dumb gorgeous planet! Plus their life cycle rules.

On our block alone wild morning glory, purslane, and buttercups sprout wild and uninvited. Broadleaf plantain and lamb’s ear too. I have loved living here these past 11 years, getting to know and notice the world around me that much better with every plant I could recognize and name—the honeylocust that’s grown from a sapling into a full-blown shade tree, purple echinacea and allium, hydrangea, spiderwort and dogwood, the maple trees that drop helicopter pods all over everything come November. That all of this and then some—everything else I cannot name, all I’ve not yet even noticed—can more or less keep itself alive? I burn. I pine. I perish.

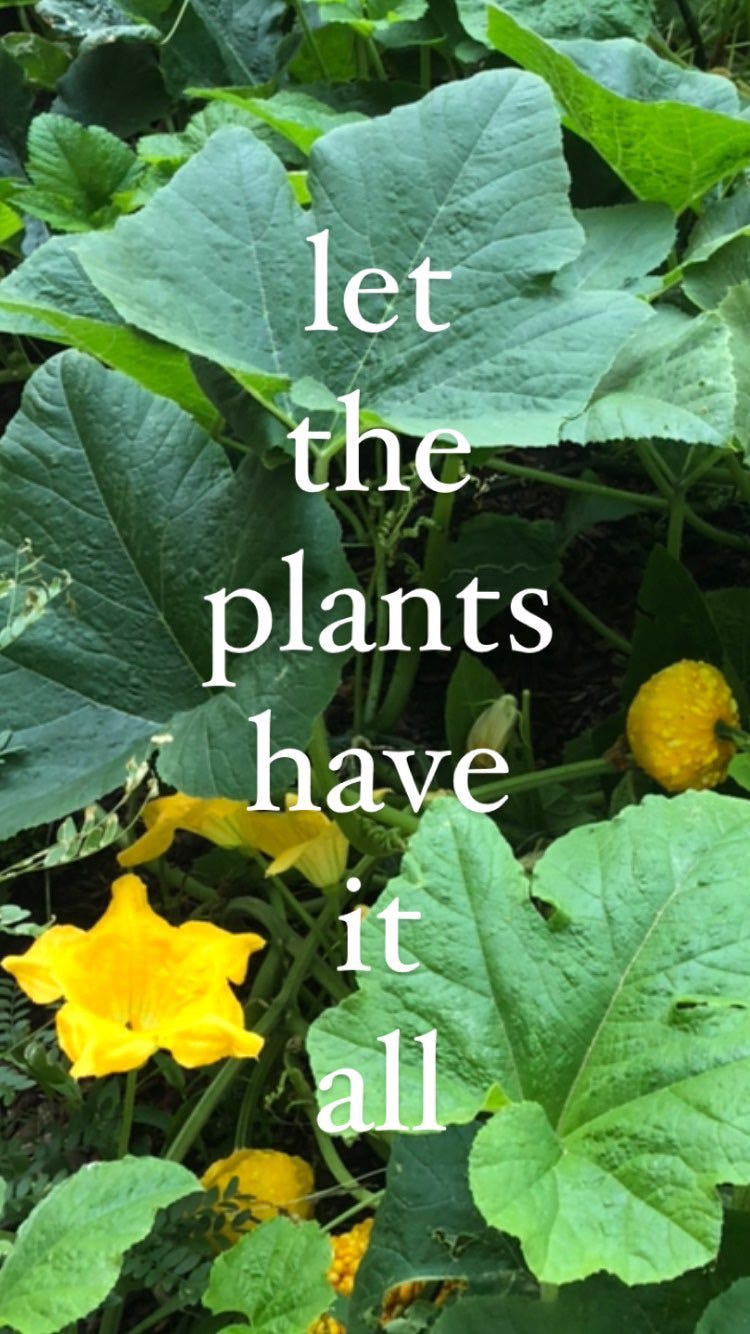

So you might imagine my demented glee upon discovering in late July, coming out of our Covid haze, a massive volunteer squash vine taking over an untended patch of earth a few buildings down from ours.

The Farmer’s Almanac urges caution when harvesting wild gourds, due to potentially higher levels of cucurbitacins, a naturally occurring chemical that can cause extreme bitterness of the flesh and violent butthole explosions for up to 72 hours. So on one hand don’t eat them, but on the other hand it might be fine. You know the risk now, same as me. We all have to make our own choices.

Passing the swelling vine each morning, I would remark to my friend who I married how wonderful it is, to see the plants winning, how excellent an opportunity maybe to hand over the keys, call it a day, give the trees the nuclear codes and plant our prayers near the roots—they’ll do a better job with all of this than we have. Which was probably the plan all along.

I’d see the squash and scream GOOD MORNING and side-eye the squirrels and say the blossoms are delicious butter-fried and served hot and the squirrels would side-eye me back. God I loved that squash.

And then someone poisoned it to death. It only took a few hours. One morning, the vine leaved green and gourd-heavy. By noon it was wilted utterly, brown and ruined to the stem. For weeks it stayed there, poor dead thing, once marvelous and alive.

I didn’t totally understand why, if there was to be a pile of organic matter in that patch of untended earth anyway, why not leave it living? I was angry. Furious even. Because the use of literal poison on a block with dogs and feral cats and kids, and wild morning glory too, and purslane and buttercups. Because enough is dead already. Because what else should claim that empty space if not a blossoming volunteer?

I try to be careful with my anger. Not to resist or deny it, or shove it down into my stomach where it can become a constant ache. I want to be mindful that I don’t direct it at the neighbor who maybe thought the vine a public nuisance—a danger to young drunk foragers!—in whose mind they were doing a civic duty. Preventing widespread diarrhea. I can understand that, and respect it. I can be grateful for it. A volunteer in their own right. Who am I to begrudge that?

Maybe it’s not that I’m angry with the mystery neighbor or even their use of herbicide in a public green space (please don’t do this), but with the way the vine was left to decompose without dignity. Torn out at the root, it could have at least become compost. A chore, I know. And maybe had I been able to see beyond my own compulsive romantic desire—a block besotted with gourds, smothered by squash and re-wilded completely with every green living thing—I might have taken it upon myself to take a cutting, if I wanted it to live so bad. I could have let it take over my life. Instead I said hello every morning and enjoyed it every day it lived.

And then I mourned it, and in this tiny grief felt what fury I needed to feel to get closer to something true, in this case: I believe in death with dignity. I believe we’re all walking each other home. And I believe that if you bring even a moment’s joy to this fuck-awful world, you deserve in the end to become compost. A seed for something new.

So many people I love are grieving right now. Family members. Marriages. Friends and friends-from-long-ago. Pets and jobs and the myth of the American social contract. Massive loss. Unwelcome shifts. I am trying to be a better friend and neighbor, a softer place to land. I am trying to not become undone at the sight of rotting fruit. I am trying to learn how, as in the tradition of my ancestors, to accept and honor death—not just of people, but projects too, and habits, beliefs and ego—as part of a sublime and brilliant design. Matter reassembled and reassembling. Energy changed, not lost.

Where a weed once grew in an untended plot, unintended for anything in particular, may something else take root. A maple, maybe, or another honeylocust. Shade trees are so important.

My apologies for going on like this. I’m still trying to be a person.

Anyway here’s a poem.

Matins

Unreachable father, when we were first

exiled from heaven, you made

a replica, a place in one sense

different from heaven, being

designed to teach a lesson: otherwise

the same—beauty on either side, beauty

without alternative— Except

we didn’t know what was the lesson. Left alone,

we exhausted each other. Years

of darkness followed; we took turns

working the garden, the first tears

filling our eyes as earth

misted with petals, some

dark red, some flesh colored—

We never thought of you

whom we were learning to worship.

We merely knew it wasn’t human nature to love

only what returns love.

Louise Glück

You write really well, Kristin.

holy squash Kristin, I adore you, the way you feel and the way you write and every single plant you mentioned and every single one you didn't mention. Thank you thank you thank you.